On the Risks and Benefits of New International Engagements

Richard LesterI write to report on how the Faculty and Administration have together been evaluating the risks of new international engagements – and strengthening our processes for doing so – in the eventful months since my last report on this subject in the Faculty Newsletter in the fall of 2018. This report also draws on more than four years of observations in my current role overseeing the international activities of the Institute, and more than four decades of service on this remarkable faculty.

Although my report is mainly about the management of risk, I begin with a larger point about the importance to MIT of international cooperation in research and education. Emphasizing the value of international scientific cooperation seems especially important today, with the world locked in a mortal struggle against a virus that is heedless of national borders. Though many governments today seem more inclined to turn inwards, close their borders, and go it alone, there could be no clearer truth than that workable solutions to the pandemic must be science-based, international solutions.

Of course, at MIT we didn’t need the current crisis to demonstrate the value of international engagement. We could simply have looked at what our faculty were doing when the pandemic struck. As of March 1, they were leading or co-leading about 2000 internationally-sponsored projects, involving 72 countries. (This total does not include the many other international activities that are supported by gifts from overseas, or by U.S. sponsors, or that have no external sponsors at all.) Or we could have looked at our student body, which today includes 3400 undergraduate and graduate students from 119 foreign countries. As President Reif observed recently, our international students are a kind of oxygen for us, with each fresh wave energizing our community as a whole.

But if international engagement is part of MIT’s DNA, it is very likely that much of what we have been accustomed to doing around the world will be more challenging after the pandemic is over, at least for a time. International travel restrictions, health concerns, worldwide economic deprivation, and social and political unrest will all create new obstacles.

And as the world begins its recovery, it will no longer be looking to the U.S. for leadership. America’s diminished reputation in the world, and the long and painful period of economic and social reconstruction that awaits us at home, will likely narrow some of our traditional avenues of international engagement.

Despite these headwinds, I fully expect that our faculty and students will remain strongly committed to learning about the world, to helping solve the world’s greatest problems, and to working with international collaborators who share our intellectual curiosity and commitment to rigorous scientific inquiry. I further expect that our more than 30,000 international alumni/ae, hailing from 170 countries, will continue to be important partners in these activities, as they have been so often in the past. And so, even though this article is about how we are managing risk, the main work of my office will continue to be to help our community pursue new international opportunities in support of MIT’s mission.

So which risks must be considered when new international engagements are proposed?

Some risks can arise in any external engagement, whether domestic or international. In both cases, safeguards must be in place against anything that could compromise the integrity and objectivity of our academic work – for example, pressure on the intellectual independence of the researcher, or attempts to restrict the publication of research results, or potential conflicts of interest and commitment. Other risks include the potential misuse of intellectual property, know-how, and data; the misuse of MIT’s name; the possibility of unwanted associations with unethical or illegal behavior by benefactors; or the undermining of MIT’s campus culture and core values. And the safety and security of our students, staff, and faculty is obviously of the greatest importance.

None of these risks is limited to international engagements, but other risks are. For example, when we work in or with certain foreign countries, we may need to consider whether our work could contribute to the infringement of political, human, or civil rights, or whether it might indirectly promote or legitimize actions by the country’s government (or by others) that would conflict with the core values of the MIT community. (These concerns may arise in our own country too. One difference is that, as an American institution staffed primarily by American citizens, we have various ways to influence outcomes at home.)

Another important consideration specific to international projects is whether they could adversely affect the national security or economic security of the United States. These are not new issues, but in recent years they have become more prominent because of the closer integration of military and civilian technologies in many fields, and because global economic competition increasingly centers on the kinds of knowledge-intensive industries and activities that are often tied to university research. The need to consider economic security is all the greater because American research universities now routinely engage in applied and translational research, participate in innovation and entrepreneurship, collaborate with industry, and generally play – and are expected to play – a more active role as engines of economic growth.

Adding to these concerns is the shift in U.S. foreign policy towards a narrower conception of the national interest, and away from the post-Cold War focus on promoting international flows of trade, knowledge, ideas, and people and supporting the global institutions that underpin the international order. As the U.S. retreats from some of its international commitments and aspirations, and as suspicion of an interconnected world grows in Washington, new questions are being raised about academic globalism.

Is it safe for so many foreign students to be coming to the United States? What will they take with them when they leave? Will they take American jobs if they stay? What are American universities giving away when they work overseas? What are foreign governments and companies really buying when they fund university research and educational programs here at home? How susceptible are U.S. universities to foreign government influence and interference?

Such questions are fueling another kind of risk associated with our international engagements – the risk of triggering actions by our own government that would cause reputational or financial harm to us or harm to our culture of openness and free intellectual exchange.

Finally, in addition to this long list of risks, we must also consider the risks – to our students, our faculty, and our institution – of not undertaking proposed new international engagements. What learning opportunities will our students miss out on? What avenues of inquiry will be closed off? What benefits of these engagements will we be unable to deliver to our partners, and unable to receive from them?

Assessing Risk

The process for assessing these risks for particular projects must satisfy several requirements. First, since most of our international activities are initiated and implemented by individual faculty members, the review process should provide support to them so they don’t have to think through these complex issues on their own.

Second, these reviews should be guided by clearly-articulated values and principles that the MIT community seeks to live by. Of course, a statement of values is just the beginning, not an end in itself. In actual situations these values are sometimes in conflict with each other, and even within close-knit organizations different people prioritize the same values differently. Some internal disagreement is therefore likely whatever the chosen course of action. That is why it is essential to have thoughtful, well-designed, systematic processes that instill confidence that different points of view will be considered carefully in each case, even though not everyone will agree with every outcome. Process should never override principle, but principle without process is a recipe for paralysis.

This is related to a third important requirement: the process should be efficient enough to avoid unreasonable delays for our faculty investigators, who are properly impatient to get on with their work and who are very often in direct competition with rivals at other institutions for access and resources.

Fourth, the process should recognize the Faculty’s stake in the reputation of the Institute, and that faculty perspectives don’t always coincide with those of the Administration. Faculty representation in risk review is therefore essential. Of course, almost nobody wants a situation in which a few members of the faculty with strongly held views can dictate the intellectual trajectory of another faculty colleague. On the other hand, even a single member of the community can make a constructive difference, as happened last year when an undergraduate student – possibly the only ethnic Uighur at MIT – organized a workshop that brought several expert researchers to the Institute to share their knowledge and insights into the current situation in Xinjiang province in Western China. This raised awareness at MIT of Chinese government repression of the Uighurs and other ethnic groups in Xinjiang and had a significant impact. Our community is knowledgeable, well-connected, and nothing if not curious. Faculty participation in risk review should reflect those assets, but also the practical limits on faculty time.

Fifth, the process must treat our prospective sponsors and donors (who may also be our existing sponsors and donors) with respect and consideration. Very few of them deserve anything less.

Finally, the process should be readily comprehensible not only to the MIT community but also to our external stakeholders, including the U.S. government research agencies with whom we work as well as their overseers in Congress. They must recognize that we are taking their concerns seriously.

Review and Decision Process

We have been working to strengthen our review and decision process since the publication in 2017 of A Global Strategy for MIT, which called for the upgrading of the International Advisory Committee (IAC) as one of its recommendations. The IAC had been created a decade earlier as an ad hoc committee of faculty and administrators to evaluate the risks of a specific international project that MIT was then considering, but over time the committee lost effectiveness. In 2017, it was reconstituted as a Standing Committee of the Institute, charged with providing an independent faculty voice in advising the Administration on major, institution-scale international engagements and policies.

In 2018, as China continued to move to the center of foreign policy debate in Washington and new MIT engagements in China were raising complicated questions of national security, economic competitiveness, and human rights, it was becoming clear that we needed to further strengthen MIT’s capabilities for thoughtful, systematic evaluation of our international projects. This conclusion was reinforced by the assassination of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi that October and President Reif’s subsequent call for a review of all of MIT’s Saudi relationships.

In January 2019 we introduced a new and more rigorous process for evaluating engagements that might pose elevated risks for MIT. For now, all engagements involving China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia are covered by this process, as are certain other projects that may also pose special risks.1

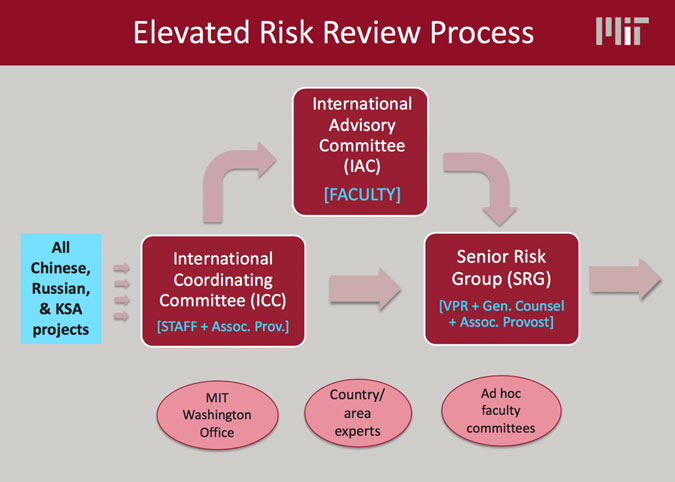

Briefly, here is how the process works. For any proposed sponsored research project, including projects involving these three countries, much of the work of assessing and managing risk is still handled routinely by our sponsored programs staff (now part of OSATT), working with the PI and the sponsor. However, when sponsored projects as well as gifts from the three countries come up, the review process now also involves three separate committees, each working with the PI – although, as we’ll see, not all projects are considered by each committee (see Figure 1).

- The International Coordinating Committee (ICC) consists of senior administrative staff with deep experience in handling international projects from legal, financial, contractual, export control, and other administrative perspectives.

- The faculty International Advisory Committee (IAC), currently chaired by Professor Rohan Abeyaratne, as just noted is mainly concerned with larger, institution-scale projects, and is particularly focused on ensuring that such projects enhance and do not divert from MIT’s core mission of education and research. Its purview is all countries, not just China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia.

- The Senior Risk Group (SRG), consisting of the Vice President for Research, the Vice President and General Counsel, and the Associate Provost for International Activities, considers projects that are judged by the ICC to require additional review by the senior administration.

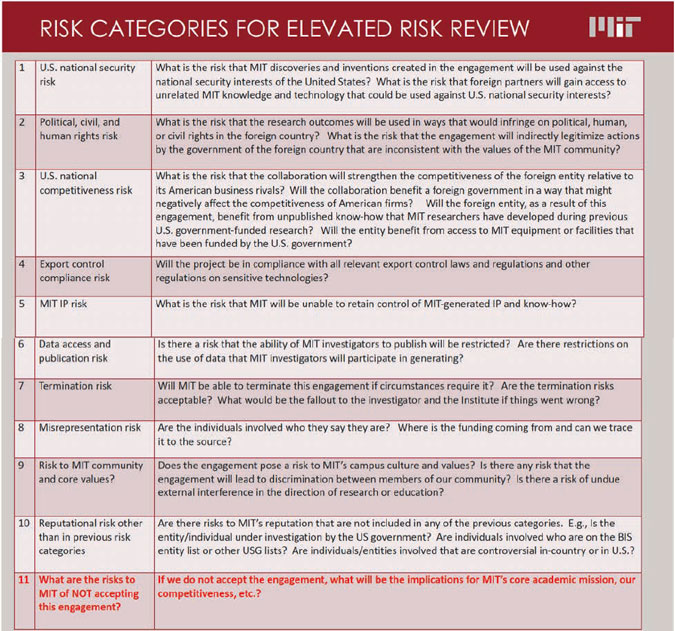

Other important inputs to these reviews come from MIT’s Washington Office; from country and regional experts both here at MIT and elsewhere who are consulted for specialist advice; and occasionally also from ad hoc faculty committees that may be convened for advice on particularly challenging issues. A key aspect of the process is to raise PI awareness of risks and to work with the PIs to develop information and approaches that may be helpful for risk management. The main questions that are covered in the reviews are summarized in the table((Following the Epstein revelations, a separate committee of administrators, the Interim Gift Advisory Committee, was created specifically to review gifts from other countries and also from U.S. sources. It is concerned with the risks of association with individual benefactors.)) .

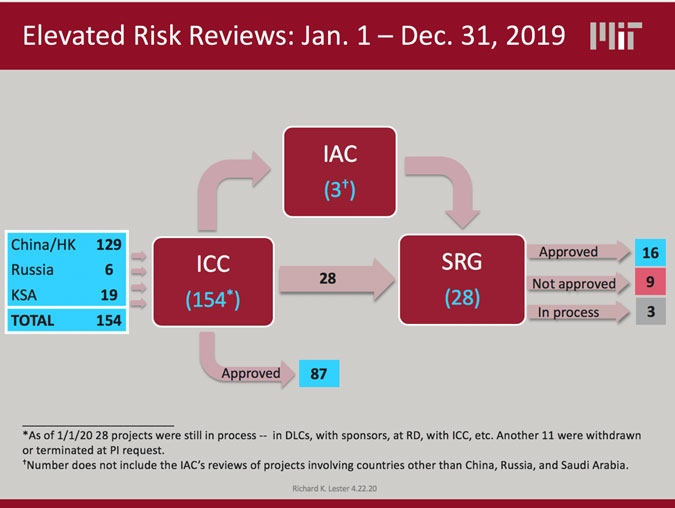

In the first 12 months following the introduction of the new process in early 2019, 154 projects with Chinese, Russian, or Saudi involvement were proposed, most of them from China or Hong Kong (see Figure 2). Most were sponsored projects, and the great majority involved just one or two PIs. All were initially reviewed by the ICC. Of these, 28 of the more complicated projects from a risk perspective were referred to the Senior Risk Group, where 16 were approved (sometimes with recommended modifications), nine were declined, and three were still under consideration at the end of the year. The IAC reviewed three of these cases (along with several from other parts of the world.) Most cases were dispatched in 4-6 weeks or less, and since parallel processing is usually possible the time actually added to the project development schedule by the new process was typically much shorter.

Saudi Aramco. A notable outlier was the proposed renewal of Saudi Aramco’s founding membership in the MIT Energy Initiative (MITEI) for another five years. I would like to provide some background on this case, partly because some of the reporting and commentary about it has been inaccurate. Aramco’s first membership term at MITEI had expired in late 2018, and the renewal was put on hold pending the comprehensive review of MIT’s relationships with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia that fall. President Reif’s announcement of the results of that review in February 2019 included two key conclusions. First, existing Saudi engagements could continue provided the faculty PIs were willing to proceed (and if they weren’t, MIT would assist with the transition). But second, all new Saudi projects, as well as renewals of existing projects, would need to be considered by the more rigorous review process that had just been introduced. In preparation for these and other decisions, President Reif requested faculty guidance on relevant general principles for MIT’s future international engagements.

The renewal of Aramco’s MITEI membership was the first Saudi-related decision to come up. The matter was considered at length by the IAC – the faculty committee – throughout the spring of 2019, and in June, after extensive consultations with the PIs and other faculty and members of the community, the IAC recommended a moratorium on the Aramco renewal, at least until further faculty guidance was forthcoming on principles of engagement. (The committee originally charged by the faculty officers to develop such guidance was dissolved before its work got started. This responsibility is now vested in the Ad Hoc Committee on Guidelines for Outside Engagements chaired by Professor Tavneet Suri, which was created last fall in the aftermath of the Epstein disclosures and is expected to report this summer.)

The IAC’s moratorium recommendation was accepted by the Senior Risk Group (SRG) in July 2019, and Aramco’s membership remained in suspension through last fall. In February the SRG acceded to a request by Professor Suri’s committee to continue the moratorium until that committee’s work is completed this summer. So Saudi Aramco is not now part of the MITEI membership consortium, and hasn’t been for more than 18 months. The renewal question is likely to come up again after the Suri committee has reported.

The Aramco case is still open, but one lesson from the work of these review committees is clear. No two situations are identical. Each needs to be considered on its own merits, taking all relevant factors into account, making often-fine distinctions that usually couldn’t have been predicted in advance, and requiring complex judgments in real time, about which different people often have different views.

Did the process work in the Aramco case? It has certainly enabled broad and thoughtful faculty input, but in another respect it has surely failed. Whatever the eventual outcome of the Aramco case, it will have taken MIT almost two years to decide. Admittedly this is partly (though not entirely) the result of the Epstein revelations and the need to work out an institutional response to them. Regardless, in the future we must be able to move with much greater speed as well as all due deliberation. On these subjects we look forward to the recommendations of Professor Suri’s guidelines committee and the companion committee on MIT’s gift processes chaired by Professor Peter Fisher. Much is riding on their ability to craft an approach that corrects the problems revealed by the Epstein debacle, while simultaneously meeting the six requirements for effective management of our international risks that I have sketched above.

And as important as these questions are for MIT’s international activities, difficult new questions will need to be faced once the pandemic is in check. For example:

- How will we work with Chinese researchers and students, both in China and on the MIT campus, during what will likely be a protracted period of strategic confrontation between China and the United States?

- How will we build new educational and research partnerships in other parts of the world, such as Africa, that are likely to be of increasing interest to our faculty and students and increasing strategic importance to the Institute?

- How will the world’s increased dependence on the digital infrastructure during the pandemic affect the future delivery of services, including education, and what should be MIT’s role during what may be a tumultuous period of restructuring and experimentation in global higher education?

- And how will we achieve our goals for global scientific collaboration, education, and problem-solving, and for bringing the world’s most talented students to our campus, while fending off attempts to close us off from the world, and when America’s global leadership threatens to be replaced by mutual distrust and rupture in international relations?

In the international arena, as in so much else, MIT will face great challenges after the pandemic has receded. But I am confident that, drawing on the collective wisdom of our faculty, we will find the best way forward. As always, I welcome feedback and input from the community.

- China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia together account for about 12% of our active international projects. [↩]