How Kafka, Not Newton, Saved My Life

Franz-Josef UlmI carry the burden of an imperial name: Franz-Josef. Austro-Hungarian, obsolete, mildly ridiculous. But this is the story of how a different Josef – Josef K., Kafka’s protagonist fromThe Trial – saved my life. Or more precisely, saved me from missing a plane and possibly far worse.

It was 2008. I was on sabbatical, teaching structural dynamics at Birzeit University, perched in the hills close to Ramallah. A quiet college town, olive groves, café murmurs – until you try to leave. Ben Gurion Airport, the only way out of the country by air, lies just 30 miles west, a short glide from 800 meters elevation to the Mediterranean plain. In theory, a 45-minute drive. In practice, anything in between one to five hours – or never. Welcome to occupation time, where military checkpoints and sudden closures rewrite the rules of physics and planning.

I had a flight at 8:00 a.m. to attend a student’s thesis defense at MIT – pre-Zoom, when you still had to show up in person. To be safe, I arranged a cab through the American Colony Hotel in East Jerusalem, where I’d dined the night before with an Israeli friend. She wouldn’t visit me in Birzeit, but she offered me her contact: a licensed Arab Israeli driver with yellow plates – the kind that can legally cross the separation barrier into Israel.

By law and design, West Bank cars with green plates are trapped on one side. My driver had the right ID, the right plates. It should’ve been simple. But I was anxious. I didn’t sleep that night. I couldn’t. I kept checking the time, packing and repacking, watching the digital clock blink its slow countdown to dawn.

The taxi was scheduled for 3:00 a.m. It arrived at 4:00.

Qalandiya checkpoint was choked. Tensions were high. My pulse spiked. I snapped at the driver – he stayed calm.

“There’s another way,” he said. “Bypass roads. Reserved for settlers.”

I hesitated for a moment, then nodded. We were bound together now – complicit. He asked if I had my passport and visa, loaded my bags in the trunk, and we slipped into the pre-dawn darkness, winding down from the hills.

Checkpoint one: the exit from Birzeit. A line of green-plated cars at a standstill. The road was closed. My driver didn’t flinch. He swerved onto a dirt road I hadn’t seen, ducked behind olive trees and construction rubble, found a path to the settler roads. No streetlights. Just the crunch of gravel and the hum of nerves.

Checkpoint two: near Rantis.

The name hit me like déjà vu. I’d been there with my students. One of them, Mohamed, had come to class with a question about the strange diagonal fractures in his bedroom wall. “They breathe,” he said. “Every day around noon. With a sound like the ground is talking.”

He wasn’t wrong.

We visited the site, “mens et manus” put into action. I recognized the signs. Fracture mechanics 101: inertia, rigidity, stored energy released through shear. But Rantis isn’t in a seismic zone. Then I saw the gas flare in the distance, behind the barbed wire fence. Shale gas. Fracking. A buried aquifer. Water pumped, then pressurized, formations fractured, ground destabilized. Mohamed’s mother – Umm Mohamed – told me her garden had dropped by 10 centimeters. Nothing grew anymore. The land had sunk. She looked me in the eye and asked if the garden would return. I had no answer.

Back in the taxi, we slowed for the checkpoint. Israeli soldiers with rifles. My driver switched to Hebrew. Too accented. We were pulled aside.

I checked my watch. 5:00 a.m.

We were separated. Standard secondary check. I told them I’d hired the driver in East Jerusalem. The soldier eyed me, skeptical. Fifteen minutes passed. My anxiety climbed to a scream in my skull.

Then: “Inshallah, we’ll make it,” the driver said.

The inshallah only made it worse.

We sped down the last stretch, passing the ghostly shell of a US army depot, a relic from the Iraq War. Down past the 1948 Armistice Line – marked by a solitary boulder – to the Israeli highway that cuts like a scalpel through contested lands.

Separation Barrier (Israeli side) close

to Qalandiya checkpoint (around 2014)

We reached the airport perimeter at 5:30 a.m. And there it was again: a final checkpoint. Heavily armed. Grim-faced. We were ordered to stay inside. Mirrors swept under the car. Doors opened. Trunk inspected. Papers examined.

Then the officer looked at my passport.

“Josef,” he said. “Like Josef Kafka?”

I blinked. Kafka had been in the news that year – Israel was arguing over Max Brod’s archives. Kafka had told Brod to burn them; Brod had disobeyed. The Trial had been published after Kafka’s death. Now the state was trying to claim his unpublished manuscripts.

I answered: “I think you mean Franz Kafka. And yes, Josef K. – the man arrested and prosecuted by a remote, faceless authority. His crime never explained.”

The officer looked at me. His eyes were unreadable.

“You’re right,” he said.

And just like that, he handed back my passport. We were waved through. I made it to my flight, barely.

I’ve never been more grateful for literature. Or for bearing the name of an empire long gone. In a world of walls and borders – and now war – it was and is Kafka – not Newton – who brings me home.

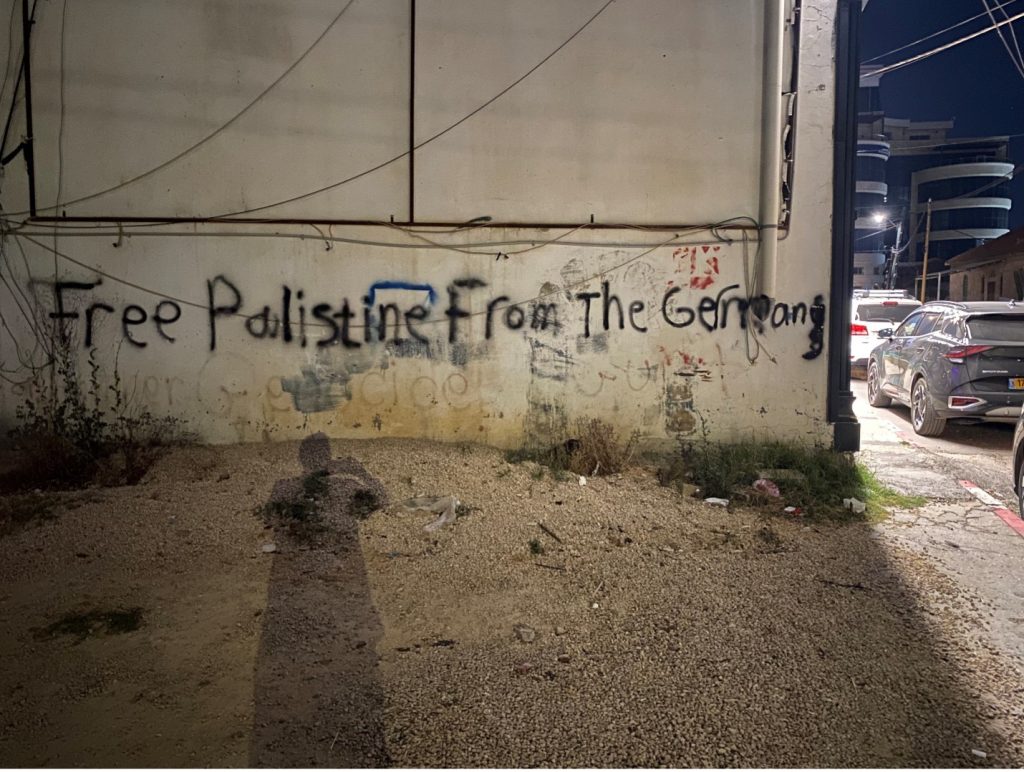

Graffiti in Ramallah, West Bank, Summer 2024