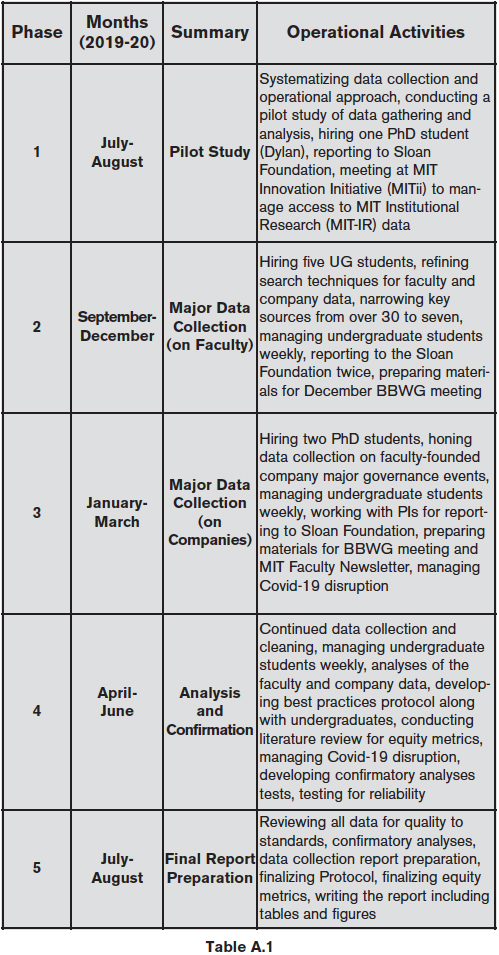

Our project encompassed five operational phases between July 2019-August 2020. The overall design and management of the study was led by Dr. Teresa Nelson and the data collection team and the production of statistics and their representation was accomplished by Dylan Nelson. See Table A.1 for an overview of the data collection and analysis process.

As we collected and analyzed these data, we confronted a series of issues around sampling, source reliability, and variable definition. We’ve included our decisions in the Data Collection Best Practices Protocol to inform future data collection. Our goal was to uncover, for each faculty member, the number of companies that person founded with founding year and the number of BOD and SAB roles they assumed either for companies they founded, or otherwise.

A. Sampling and Coverage

The BBWG Chairs, Dr. Murray and Dr. Nelson, selected seven MIT departments for study based on the assessment that these were most focused on work related to biotechnology. The departments were: School of Science – Biology, Brain and Cognitive Science, and Chemistry; and School of Engineering – Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Biological Engineering, Chemical Engineering, and Materials Science. Our study originally included the Physics Department, but this was removed after Phase I data collection showed low relative commercialization activity rates. The data identifying the faculty of these departments were obtained from the MIT Institutional Research department and included name with employment year, assigned department, sex, rank at hiring, and promotion timing.

While the research as originally proposed presented a research design focused on biotechnology firms and their founders, we came to see quickly once the project got underway that departments were a better base for study. Faculty, over the course of their careers, move in their research across blurry industry boundaries while department assignments are generally reliable for faculty over time. This choice significantly expanded the number of faculty we studied, though we took it as the best solution to describe faculty governance in biotechnology.

Our focus on tenure-track, full-time, current (June 2019) MIT faculty meant we excluded multiple groups from our main analyses including visiting professors and lecturers as well as faculty who had left MIT, retired, or died. We believe this sampling choice strengthens the rhetorical heft of our work vis-a-vis corporate leaders and venture capitalists by highlighting current human capital resources. However, inspired by the career of a female Biology professor who had founded multiple companies before her 2016 death, we developed a confirmatory analysis to this work by observing the governance commercialization activity of all full-time tenure-track professors employed at MIT 2000-2018 for the sake of comparison. Results of that test are described in the confirmatory analysis section below.

The first primary data collection entailed collecting and recording data for 337 faculty members for founding and BOD/SAB membership in the years 1974-2019 (1974 was the earliest year of activity for any current faculty member). This scope also represented a broadening from our initial proposal which had taken 2000-2019 as its time focus. This change was made because the early days of the biotechnology industry and MIT faculty commercialization activity is an interwoven story.

The second major database we developed centered on all of the companies founded by these 337 faculty members. While we were able to reliably date company founding through corporate registration records, we found it difficult to accurately date BOD membership dates and SAB membership and dates of membership as many of these appointments lived outside of the digital record, particularly in the early years. We were most concerned with, and paid particular attention to, the threat of false negative bias regarding closed, older firms that would be least likely to have shared their data via the internet. To combat these concerns, we ran reliability tests outside of key data sources.

B. Data Source Selection and Reliability

To establish our data sources, we compiled a descriptive record of 35 publicly available data sources that could serve the project. These were drawn from categories such as general business (e.g., Pitchbook, Capital IQ), specialized business (e.g., Xconomy), business press (e.g., Factiva, Wall Street Journal, MIT news sources), general internet searches, company websites, books, and professional information sources (e.g., CVs, LinkedIn, MIT departmental websites). We then conducted a series of tests to reduce this array to seven key sources that were shown to provide supplemental information with integrity.

We analyzed the integrity and uniqueness of our datasets three times: during our pilot study, during our mid-project reflections, and at the end of our study. The overlap of information between our key sources was not highly patterned and so we retained the seven key sources throughout the study. As a general rule, we gave the most weight to statements faculty made about their own record, data on the MIT website, legally required data, other company sources, press sources, other sources. After the initial database was compiled, we conducted second level searches, meaning that for each identified role, other roles with the same company were confirmed or denied. Further, for each company founded, public records were sought to confirm faculty member governance activity. We estimate our number of individual searches as greater than 15,000, including reliability tests. We believe that our data exceeds the standard for academic publishing in terms of completeness and reliability.

C. Measuring Faculty Governance Commercialization

While many methodological issues can be managed through triangulation and validation, basic definitions provide the roadmap for the work on an ongoing basis. Throughout the study, we excluded nonprofit organizations, even if they offered a product for sale. We also excluded certain for-profit companies including consulting companies, venture capital companies, and non-science and technology related companies. We did include international companies where we found them, but we are not certain of our reach internationally because of the U.S. bias of our data sources. We made this decision in part because companies included were founded by female faculty, our segment of greatest interest. Also, because the companies sometimes blended U.S. and other nation status through their governance activities (e.g., founded in one country, IPO’d in another).

Another substantial measurement issue involved tracking down company name changes to avoid double counting. Name changes are common because many biotech firms, especially compared with other start-ups, adopt the name of their invented or most successful product initially, and then are persuaded to change upon growth, investment, or acquisition. Sometimes the distinction between a name change and the identification of a separate company is a judgement call. If counted twice, we required that a morphed second company be substantially different, as we would in the case of some spin-offs. This practically required doing a secondary test of all companies related to a specific faculty member after the initial database had been created, to confirm that these were, in fact, unique companies. Some databases, like CapitalIQ, were more useful for tracking the historical development of firms. Searching on Google for both names together was also useful.

D. Defining Faculty Characteristics and Governance Commercialization Activity

Membership on boards of directors was relatively straightforward to identify because of strong institutionalization – there is less ambiguity about what it means to serve as a director as it is a legal company classification and reporting is mandatory. There were, however, definitional and practical challenges in determining company founders, particularly for this set of companies.

In practice, firm founding is a socially constructed, not legally defined term (Nelson, 2010). The attribute of “founding” can be used to describe a range of levels and types of relationships occurring along a spectrum of activity from innovating the fundamentals to serving as an executive officer of the company that has transformed that innovation to a commercial product or service. This work gets ambiguous with science and technology companies particularly when a faculty member is identified as a “scientific founder” (not a “founder”) as they were responsible for the underlying discovery, or for supervising graduate students or postdocs who are themselves the actual innovators, but who are hands-off in terms of the discovery’s development as a commercialization act. To operationalize this concept, we required a concrete report of founding from a key source taking company and faculty member self-identification as a “founder” as reliable evidence. We came to see that the more prolific faculty were in commercialization, the more likely they were to be mentioned as a “scientific advisor,” perhaps due to legitimacy value.

Our third category of governance activity, SAB membership, was the most difficult to establish. Companies vary in having a scientific advisory board and in reporting its existence and membership publicly. SABs are not legally required, and public databases do not include the role reliably in their company reports. There is also a classification issue between “scientific advisors,” often more informal and ad hoc in comparison to the more formal “scientific advisory board” and its members. We measured the latter requiring that at least one key source or secondary source list the faculty member in this role. We also coded “technical advisory board,” a term more common for engineering related companies, or other similar names, as SABs. In conclusion, we are confident that the SAB role designations included in our database are accurate, and we expect that there are missing entries representing SAB role service that have not been officially announced.

E. Defining Company Characteristics and Major Governance Events

We faced three major conceptual issues in defining MIT faculty-founded company major governance events beyond those described in section C above (e.g., non-profit, non-scientific discovery, etc.). The first concerns company founding date. Because published year of founding can conflict across data sources due to varying founding “moments” such as company legal registration or invention patent filing dates, we used the first year that the company was registered in Delaware as our variable, since over 90% of companies register there. Where registration in another state (often Massachusetts or California) also existed, we confirmed that the Delaware date immediately preceded or repeated the other registration date, otherwise we sought secondary confirmation. For collecting data on founding date, the opencorporates.com website was useful.

Our second challenge in this category concerned providing some evidence regarding the scale and impact of the company founded. Did the company: 1) establish itself, 2) manage to share its innovation with the world, and 3) how profound was that impact? This research accomplishes point 1, provides evidence on point 2, and fails on point 3, except insofar as one can make the claim that companies that grow very large in their market reach have successfully done important work by touching market members widely and/or deeply. We envision a follow-on study that could investigate these data by science or technology base, versus departments. Such a study could also develop additional performance measures that would move closer to a true “impact” assessment.

By investigating how faculty founded companies established themselves within the entrepreneurship activity stream, through initial public offering (IPO), acquisition, closure, and/or venture capital investment, we provide evidence to use in answering these questions. The amount of venture capital investment can be taken in part as a measure of the market’s belief in the innovation’s ability to reach markets widely and/or deeply over time.

Note that these “company outcome” variables are not exclusive. Some faculty-founded companies went through an IPO but later went bankrupt, others were acquired and later went through IPO, etc. The process of collecting this data over time is tedious and requires expertise in entrepreneurial firm capital structure. We collected investment level data for each company across three leading data sources, then categorized the companies into reasonable VC investment ranges to smooth differences. We did not collect acquisition valuation data because this data is held closely by acquirers in most cases in the private market (Kaplan & Lerner, 2016).

For a handful of firms, it was hard to determine whether they were open or closed, as their current website revealed very little activity over the last two to five years (potentially “living death”), but we deferred where there was no concrete evidence of closure to call them still “open” as faculty life is very busy and projects may sit for some time. Ultimately, the closure status is “caught” as states, including Delaware and Massachusetts, will proceed with an involuntary revocation after not receiving required filings, which, without resolution, would prevent a company from continuing in business. In operationalizing closure, we included voluntary closure, bankruptcy, evidence of living death, or final asset sale, a case where remaining company assets are “acquired” in a way much different than a true acquisition of growth assets.

The third major issue regarded the structuring of our database in terms of companies and faculty was the assigning of co-founded companies to departments. This was not an issue when both or all three co-founders were in the same MIT department. To manage this variable issue, we decided to code these firms as “cross-departmental.” In terms of assigning companies a “sex of founder” variable, we chose to present the handful of companies founded by one female and one male in their own “cross-sex,” rather than simply assigning these two firms to either binary sex category. We thought these collaborative categories were interesting as data points. We did not record non-MIT faculty co-founders in any way.