I jokingly call what you see in the photo the “derobotizer” setup (more on that below). I made it for my wife after the pandemic forced her to shift to working mostly online via Zoom – like all of us educators. She happens to be a biotech executive.

This setup is about as portable as it gets. I hooked it up in minutes using off-the-shelf parts on top of a tray serving as the base. It’s easy to use, makes you look like a real person on any video-conference app, and allows you to perform serious remote-world magic. Anyone can set it up.

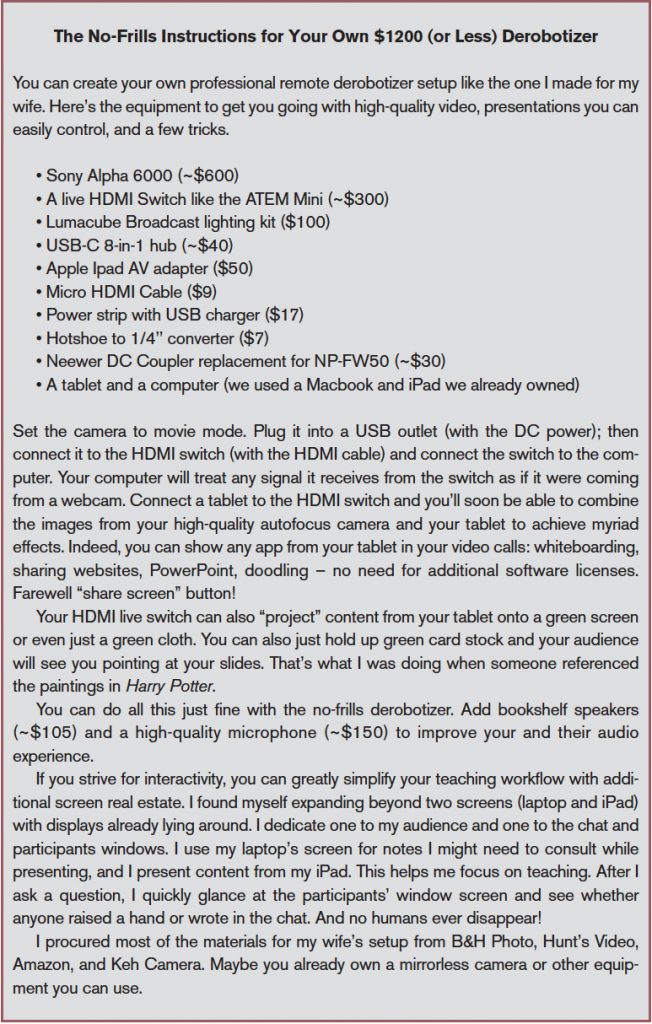

I think every committed educator needs something like this. Below, I offer some no-frills instructions for creating your own professional remote derobotizer setup – or you can go even further with the derobotizer I made for myself. But first allow me to explain why and how I got to the point of derobotizing in the first place and why I think educators will need to master this new medium in the “new normal” that follows the vaccine rollout.

It begins with the meaning of technology. This has nothing to do with pretend-playing with a product, or enslaving users for advertising dollars. I set out to solve a problem, and technology was a tool to begin to solve that problem in the very way MIT founder William Barton Rogers intended – to extend our power over nature. In this instance, it was to extend our (humans’) power over nature just enough to overcome pandemic fatigue, and perhaps help students find solace in their education.

You don’t need to settle for the robotic, pixelated version of yourself the pandemic has cornered you into becoming. You do not need thousands of dollars, specialized knowledge, minimum-viable startup-oil, or some youth potion. Indeed, you can get started right away.

I worked my way to a home video setup that allows me not only to show slides but hold them in my hands and point at them with my fingers while my students – in real time – see slides magically change and experience the same awe Harry Potter did the first time a moving picture winked at him. I learned new tricks as I strived to adapt my teaching, management, and presentation routines – as evidenced by the “magical slide” employing a trick that I used in the classroom and in conferences such as my keynote presentation at the 2021 KEEN National Engineering Unleashed conference.

Technology in Service, not Hinderance, of Humans

Lecture 1, I pulled up my slides, turned my head, and discovered the classroom – and all my students – had disappeared. About 40 humans had just dropped from my sight and all I saw was Catalina Island. I knew I had to keep my cool.

In 2020, all the tools, labs, experiences, and whatnot we educators have honed to shape minds stopped working. Overnight, the need for Zoom created all manner of cognitive traps, including my students’ disappearing act. Many of us transformed into robotic-sounding, pixelated versions of our former selves (hence my use of “derobotizer”). It’s as if we woke up one morning to Plank’s constant suddenly becoming 1 (ask a physicist friend about that).

If your experience was anything like mine, the sum total of the advice you got about making this profound shift was to avoid putting yourself in front of a window, lest your students take you for the silhouette of some confidential informant in a made-for-TV crime documentary – in other words, nothing to prepare you for the new reality-shattering normal of things.

Truly educating someone takes more preparation than most of us admit to ourselves. Preparing and delivering an engaging, rigorous educational experience requires enormous brainpower to gauge the audience in real time, keep its attention, and be ready to react to wherever the conversation may take you while still hitting all the main points. You have to be prepared to handle whatever might unfold in the multiverse. No two cohorts are the same, and any two editions only resemble one another. Whether you call it education, mastery experience, or flipped classroom, it takes a fully engaged human brain, not a parrot. That’s why merely surviving Zoom is no replacement for education. The fact that so many think it might be reveals that we may have begun to go full-on robotic well before bats brewed Covid-19.

We’ve been getting a sneak peek into the despair, boredom, confusion; atrophied critical thinking, addiction to good-sounding recipes, and general loss of nuance that begets a world in which education is flat, abstract, pixelated, and cursed to a daily face-off with other screens – a world devoid of actual education, and where instead it feels as if everything’s become marketing or branding.

Sadly, the pandemic has also made it easy to imagine learning minus the teacher and the action – perhaps with a recording, some app, this or that masquerading as “AI,” and peer-grading. Education administrators have turned to anything labeled “Ed Tech” to appease their boards. We risk losing the meaning of education to the same breed of opportunists turned startup-oil salesman that would advocate the kind of minimum viable “tech for education” that will “help” education just the way “social” media made us more “social.”

I know my students appreciated the commitment to education more than they would have accepted the justifiable excuses had I made them. The lesson: this is no time to take education for granted. It is the time to double down on every reason we still call it educating (not just certifying).

Pretending Reality Hadn’t Been Distorted Is Futile, So Distort Your Own Reality

Back to Lecture 1. I’m still watching Catalina Island. The next few seconds would be crucial. The classroom didn’t really disappear; rather, because I shared my slides, the Zoom window with students had hidden itself somewhere. To my dumbfounded brain, though, busy choreographing my teaching act, the entire episode felt pretty much as if an actual physical classroom had disappeared.

I should mention that my class is particularly unsuited for this remote world – or so I thought. It is deeply experiential, based on research, open ended, and combines teamwork and lectures. I designed and run it as a mastery experience, with a flipped classroom pedagogy. It is also a truly cross-discipline, cross-School elective (my students come from all over MIT and Harvard). We take technology advances and papers and ask ourselves the tough questions: Now that we know that is possible, what problem can we solve that we couldn’t before? What will it take to assemble and fashion the technologies and organization to do it sustainably? You can learn all about it here.

Students who take my class sometimes come to dread that I refuse to give them a recipe. Those that persevere end up thanking me for liberating them from the childish recipes and slogans that populate the conflation of entrepreneurship and innovation that has taken over academia. I cannot afford a bad performance early on, though; my class is an elective – the only way to stay truly multidisciplinary in our modern educational system. If, based on that first encounter, students dropped the elective, I’d forfeit months of work making the class known to students across MIT, which is how I materialize my multidisciplinary mission. Imagine, then, my anxiety over the disappearing classroom.

We were set to work in teams on projects ranging from, among others, quantum computing and obfuscation to biotechnology manufacturing, artificial intelligence, new drug delivery systems, and new battery technologies. I could not imagine leading teams of daring students for an entire semester while in fear of sharing slides. Nor could I imagine surrendering to becoming a voice-over to my slides. After all, education isn’t about accompanying my slides or a textbook or a recipe with voice, but about freeing students from the tyranny of recipes and gifting them with increased skills to use their own critical thinking. Right?

I managed that first day, and became better quickly (see some technical guiding principles in the box, below). Along the way, I learned to present in a wall, standing up, walking around my slides, and knocking at them to prove my points were solid; present while holding slides in my hands that moved like the paintings in Harry Potter; present while seeming to doodle in mid-air; use my iPad as the whiteboard while still showing my camera’s image; and countless other tricks, all done from home with a setup like the one in the photo.

That setup (see instructions in the box, below) allows you to go back and forth from slide to image with the press of a button. With picture-in-picture (another button), you can display both your camera image and iPad. A tablet pen lets you doodle on your slides.

Sure, you can do all that on Zoom, too. It’s also true that with enough patience, you may be able to cut a small tree by chewing at it, although I don’t recommend that. Technology isn’t only about doing new things; it’s also about making complicated stuff easier to handle, which this setup accomplishes, so you can focus on teaching and learning – the important stuff.

Pushing the Limits of the New Reality for the Sake of Teaching and Learning

With the newfound confidence that comes from knowing the classroom wasn’t going to disappear again, came an opportunity to learn how to educate online.

I discovered that structuring my content by weeks rather than modules or individual lectures helped students measure progress and overcome more easily the disorienting nature of living in confinement. This required I rewrite my syllabus but also helped me prepare to react to where students are in their learning and coping – we all get hopelessly lost online, so reminding students every other week where we were in the class helped.

One full hour online carries only about 20-30 minutes of the equivalent in-person content. You need new strategies to convey content. I broke lecture content into 20-minutes-or-less chunks, changing the activity from segment to segment. I created plenty of new breakout room activities designed so the content would emerge through discussion when we reconvened. Students crave interaction, so I used breakout rooms with tactical assignments that helped students share their progress, and meet one another.

I ended up finding a lot of good uses for the Canvas software, particularly the ease with which it creates websites to offload content I might have delivered in person in the past (and thus create more time for interactivity) and, unexpectedly, as a live conference organization/management system.

The home front matters too! I dread the notion that my family could be together at home isolated from one another by a forced addiction to Zoom. I found ways to help my kids help me. I enlisted the invaluable help of my 11-year-old daughter and 8-year-old son, who became my honorary teaching assistants. That, incidentally, was the smartest decision of all. It helped us all fight isolation and insularization together.

I learned also a few things not to do. The immediacy of online polling results can easily kill the conversation. When needed, I poll the old-fashioned messy way. I do not to record live sessions for students; I’m not a parrot, and for me education isn’t about giving slides a voice-over but about the interaction – I have a whole different workflow to create recordings. In non-pandemic times, I love when students feel they can drop by with questions at any time (I learned from Patrick Winston). In pandemic times, that meant going beyond Slack and giving my cellphone number to students. Formal peer-to-peer assessments did not work for me, but giving students a guided opportunity to comment on each other’s work worked wonders – provided I did not make it an assignment but an activity.

Learning new ways

Most often, reality matter-of-factly proves our theories wrong. Sometimes, it shreds a confirmatory data point. I think of what I teach as the practice of how to solve problems that matter starting with what you have, and with technology (new or old) as a malleable tool; that is also the subtext of my book Innovating (MIT Press, 2017). I wrote Innovating to share how to do just that after decades exploring, testing, refining, teaching, and adapting the subject matter to academia and industry worldwide. That practice helped me and my students in this pandemic.

The student teams worked smoothly, better than in many other semesters – even though the members had never met in person – and so much so that we dared try new things.

At the end, they presented advanced technologies to a middle school Zoom meeting packed with 300 students and faculty in what was a profoundly inspiring event. They glimpsed into a future: colonizing Mars with batteries and bio-manufacturing; quantum computing in space; a game to repurpose technologies and innovate while playing. Without the pressure to pretend-play that everything is a “startup pitch,” student teams found genuine ways to explain a future that technology can help build. I now want to end my class like that every year.

Two days later, I closed the first ever homemade remote edition of iTeams – that’s the name of the course – by entering a forest that had “magically” grown in a utility closet in my office (you can see a video of it here). https://vimeo.com/548246873/c40f2f23c0

I learned, too, especially about technology simply serving the objective of educating – and that it is urgent we share more broadly our gift for fashioning technology into tools to come to grips with problems that matter.