On the 20th Anniversary of OpenCourseWare: How It Began

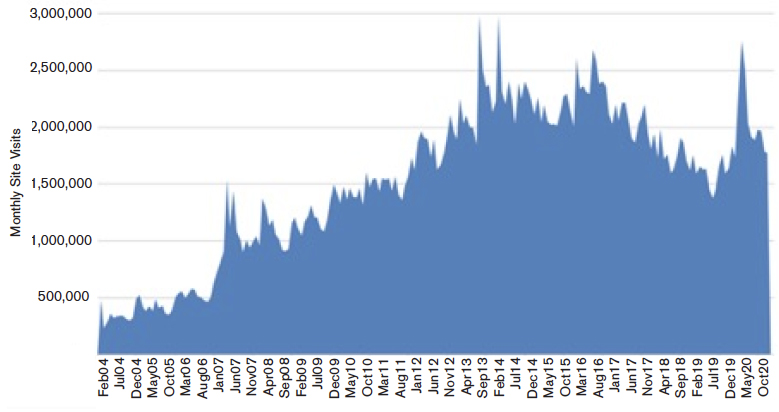

Hal Abelson, Shigeru Miyagawa, Dick K. P. YueOn April 4, 2001, MIT President Charles Vest announced that the Institute would make course material from virtually all undergraduate and graduate courses “accessible to anyone anywhere in the world, through our OpenCourseWare initiative” (Vest 2004). The decision defied the dot-com trend in academia at the time and garnered a front-page story in the New York Times. Today, MIT OCW offers high-quality educational materials from more than 2,500 MIT courses – the majority of the MIT graduate and undergraduate curriculum, spanning all five MIT Schools and 33 academic units. One million unique users from every corner of the globe visit ocw.mit.edu each month (see figure), making it one of the largest online educational sites in the world.

In the beginning, OCW was “just an idea – an informed leap of faith that it would be the right thing to do and that it would advance education” (Lerman 2004). OCW had a humble beginning in a small faculty committee formed in the summer of 2000 to develop a proposal for financially sustainable online course dissemination. The idea of giving away the course material was not even remotely part of the group’s charge.

What happened that led the committee, at the very last moment before the report deadline, to advocate for openness, and how this idea took on a life beyond anyone’s wildest imagination, is a study in how an academic institution can tap the talents of its faculty, delve into its values, and exercise academic leadership to forge an innovation that, in tandem with the technological and societal forces of the time, takes on global significance.

Why Openly Share Teaching Materials?

Shortly after the announcement, a faculty member told us, “The day MIT announced OCW was the proudest day of my career at MIT.” This sentiment was shared across the Institute and led to a vast majority (as high as 75 percent) of tenured and tenure-track faculty contributing their teaching material to OCW (Abelson et al., 2012). It is not surprising that the idea of openness resonated with the MIT faculty – sharing knowledge is a core value of the Institute, as articulated in the MIT mission statement1:

The Institute is committed to generating, disseminating, and preserving knowledge, and to working with others to bring this knowledge to bear on the world’s great challenges.

MIT traditionally fulfilled this mission largely through basic research. Now OCW also substantially supports the mission.

The committee that proposed OCW explored a number of possibilities. Having failed to come up with financially viable and exciting e-learning options for MIT to pursue, the members reached deep into the school’s core values and hit on the idea of opening up the Institute’s teaching materials. When asked why MIT decided to give away the teaching materials for free, Charles Vest said:

“When you share money, it disappears; but when you share knowledge, it increases.”

This captures the essence of OpenCourseWare and celebrates the principle of openness that is at the core of MIT’s mission.

Origins of OCW

The emergence of the World Wide Web coupled with the dot-com frenzy of the 1990s sparked a boom-town atmosphere among leading universities, stimulating ambitious ventures in distance education. Some of these were UNext (which began work with Stanford, Chicago, Columbia, and CMU), Pensare (Harvard Business School and the Wharton School of Commerce), Caliber Learning (Georgetown, USC, Wharton, and Johns Hopkins), the Princeton-Oxford-Stanford-Yale Alliance for Lifelong Learning, Columbia’s “Fathom” Knowledge Network for online learning, and e-Cornell. e-Cornell is the only one of these ventures that survives today.

MIT, not immune to these currents of change, commissioned several strategy councils to chart a course through the murky future. These included the “Committee on Education via Advanced Technologies (EVAT)” (1994-1995), the The (First) Council on Educational Technology (1995-97), and the Task Force on Student Life and Learning (1996-1998).

The final committee reports revealed two very different visions. On the one hand, there was the promise of expanding MIT education worldwide, “the death of distance” as the EVAT report trumpeted. On the other, there was the Task Force’s thorough endorsement of the essential role of informal education and the residential campus as an essential environment for student life and learning, and a vision of the future where

“MIT will continue to attract the best students, faculty and staff by offering an exciting mix of excellent educational and research activities that take place within a residential campus community” (MIT Task Force on Student Life and Learning, 1998).

Faced with this divergent guidance, the MIT administration chartered another task force, the (Second) Council on Educational Technology, to seek a synthesis. The goal of the Council would be “to enhance the quality of MIT education through appropriate application of technology, to both on-campus life and learning and through distance learning” (MIT News Office, September 29, 1999).((“Provost announces formation of council on educational technology,” MIT News, September 29, 1999. Available at http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/1999/council-0929.html.))

The Council was co-chaired by Provost Bob Brown and Computer Science Professor Hal Abelson. It chose to work with an outside consulting firm, McKinsey and Company, in defining and evaluating MIT’s strategic options in a changing educational environment. The idea of working with an outside consulting group was suggested by Sanjay Sarma’s partner, Dr. Gitanjali Swamy, who worked for Booz Allen Hamilton. In Sarma’s discussions with her about MIT, she convinced him that getting a professional consulting team to do an MIT-wide strategic plan, pro bono, would offer a better perspective. At the end of a three-month engagement, the MIT-McKinsey team had outlined a few strategic themes for possible implementation. It chose the banner of lifelong learning and recommended that MIT undertake a study to launch “Knowledge Updates,” minicourses based on MIT’s strength in cutting-edge science and technology, designed for MIT alumni.

In April 2000, Provost Brown created the Life-Long Learning Study Group, led by Associate Dean of Engineering Dick Yue, charged with formulating a plan for “Knowledge Updates,” with up to $2 million in startup investment to launch an enterprise that should be financially self-sustaining within two years (Abelson, 2008). Shigeru Miyagawa was a member of this group. The group chose to engage Booz Allen Hamilton to conduct a detailed analysis of options and business plans for the proposed initiative. Given the specific charge, this group pursued the Knowledge Updates project with the genuine hope of creating a successful enterprise.

By fall 2000, with the deadline for a final report looming, the group was ready to recommend the rollout of MIT Knowledge Updates (KUs), which, thanks to the support of Booz Allen Hamilton, was backed up by extensive market survey and analysis and a detailed financial model. The proposal was that, in order for a meaningful impact and reasonable chance of financial sustainability in the near future, MIT needed to pursue KUs at a significant scale at the Institute level. Some in the group, including Miyagawa, had expressed concerns about KUs from early on. There were many risks and unknowns: Would the venture divert resources from MIT’s core mission? Would it dilute MIT’s brand? Would this negatively impact the Institute’s culture and faculty unity? Given the late start relative to many of our peer institutions in this space, what were the chances that we would be successful? These and other questions were discussed extensively in the group’s final deliberations.

After months of strenuous work, what was on the table was reasonable but far from spectacular. Many on the team had harbored aspirations that this could be a unique opportunity for MIT to exert leadership, set an example for its peers, and make a truly significant impact. In contrast, the KUs struck them as underwhelming. It was against this backdrop that the idea of OCW was born and took hold. In one of the last meetings of the group in October 2000, Yue laid out the basic idea that MIT could aim for leadership and impact by simply giving away all the teaching material without charging for it. That was to be the recommendation to MIT and that MIT would make an institutional commitment to making this happen. The idea was remarkably simple and could be articulated succinctly. Once understood and embraced by the group, they quickly worked out some of the key issues and prepared the final recommendations and report, which followed essentially what was originally proposed in that October meeting. They came up with the name OpenCourseWare, drawing both the name and inspiration from an earlier MIT effort, open source software.

OCW Is Born

In October 2000 the Life-Long Learning Study Group presented its report to the Academic Council. The report contained a treasure trove of data gleaned from interviews with 50 external organizations engaged in e-learning, responses to an extensive survey sent to 2,500 alumni (deemed potential clients for Knowledge Updates), interviews with 60 MIT faculty members who had already put their teaching materials on the Web, and a series of elaborate business models, all done in collaboration with a team from Booz Allen Hamilton. The report included – “almost as an afterthought” (Abelson, 2008) – the following suggestion, fundamentally defying MITCET’s original charge to the group:

A revolutionary notion of OpenCourseware@MIT could radically alter the entire lifelong learning and distance learning field and MIT’s role in it and should be seriously considered.((Lifelong Learning Study, Summer 2000. Report to the MIT Academic Council Deans’ Committee, October 17, 2000 (unpublished).))

Guiding Principles and Institutional Leadership

The committee agreed on a principle that became a cornerstone of OCW: all materials offered should be cleared of copyright so that users can freely use them to learn and to teach. When Harvard Law professor Larry Lessig and his colleagues launched Creative Commons in 2001 to furnish licenses for appropriate use of copyrighted material free of charge, MIT OCW adopted this mechanism for virtually all its materials. Abelson, who was part of the group that launched Creative Commons, worked between the two nascent initiatives to arrange the license adoption. OCW became the first institutional project to use Creative Commons licenses. Conversely, several OCW requirements helped shape the terms of the newly minted Creative Commons licenses.

The principle of faculty governance was central to the planning phase of OCW. Chancellor Larry Bacow told the OCW planning group that MIT could not announce the initiative without extensive discussion within the community. The group met with 33 departments and major administrative units. Although most voiced support, some raised concerns, such as the risk that OCW could devalue MIT’s reputation by putting up low-quality material (Abelson, 2008). The culmination of these discussions was a presentation at the February 2001 faculty meeting, at the end of which President Vest spoke with conviction about OCW. The record of the faculty meeting states that, noting the trend toward commercialism in higher education,

MIT could be a disruptive force by demonstrating the importance of giving information away. Vest noted that in the 1960s and ’70s MIT had a big impact on education, not only from textbooks that were published by the faculty but also from the course notes, problem sets, and other materials our graduates took to other institutions where they used them in their teaching. OCW, he stated, gives us another chance to make such an impact.((MIT Record of the Faculty Meeting of February 21, 2001. Online at https://web.mit.edu/dept/libdata/libdepts/d/archives/facmin/010221/010221.html.))

Thus, while faculty governance was at the heart of decision-making that moved the initiative forward, academic leadership played an equally important role, and MIT was blessed with strong and open-minded leaders. The role of President Vest was obviously critical. Others who played a key role in guiding OCW went on to leadership positions at major universities. Provost Brown, who shepherded the discussion from the outset, became president of Boston University in 2005. Rafael Reif, who took over as provost after Brown and continued to nurture OCW, became the 17th president of MIT in 2012. Chancellor Bacow, who called for the extensive discussions to get as many on board as possible, became president of Tufts University in 2001 and of Harvard in 2018.

Off and Running: Funding, Staffing

Funding

Giving away the course material for free does not mean that there is no cost to set it up and operate. Fortunately, Vest’s overture to William Bowen, president of the Mellon Foundation, was met with enthusiasm. Bowen in turn contacted Paul Brest, president of the Hewlett Foundation, and the two foundations agreed to fund OCW. Ira Fuchs, the Mellon Foundation program officer for the grant, said that the foundation “really bought into the ambitious and unique nature” of OCW (Walsh, 2011, p. 62). Without this generous funding, OCW would not have seen the light of day.

Staffing and Implementation

Once the grant proposal to Mellon and Hewlett (co-authored by Brown, Abelson, and Faculty Chair Steve Lerman) was approved and an initial $11.5 million awarded, Anne Margulies, former CIO of Harvard, was hired in May 2002 as OCW executive director. Her first task was to create a 50-course pilot by September of that year (Walsh, 2011). She recalls, “All eyes were on us. There were lots of skeptics, but the overwhelming majority were excited.”((Interview with Margulies on March 7, 2016.)) Margulies participated in the 2002 UNESCO Forum on the Impact of Open Courseware for Higher Education in Developing Countries, held in Paris. Many university presidents and rectors from developing countries were in attendance, and their message was “Thank you, MIT.”

In addition to creating a 50-course pilot in her first four months, Margulies had to complete posting 500 courses by October of 2003. This deadline, imposed by the funders, had to be met before delivery of the balance of funding. To the credit of Margulies and her team, which at the peak numbered 50 full-time employees and outside consultants (Walsh, 2011), the deadline was met and Hewlett and Mellon awarded the remaining $16 million, which made it possible to complete the OCW posting of 1,800 courses by 2007.((This was the original target, and was celebrated at the time (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbQ-FeoEvTI).))

Margulies left in 2007 to become assistant secretary for information technology and CIO for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; since 2010 she has been vice president and University CIO at Harvard. Cecilia d’Oliveira, who had been the director of technology for OCW, took over, overseeing continued growth with new programs like OCW Scholar courses and OCW Educator. After her retirement in 2018, Curt Newton, a long-time member of the OCW team, was appointed as director.

Impacts at MIT

OCW has significant and beneficial impacts on campus at MIT. Students use OCW resources such as problem sets and exams for study and practice. Freshmen report that they checked out the school by looking at OCW before deciding to apply. Because faculty have easy access to the course material that their students use in other courses, OCW serves as a broad communication channel among faculty. And alumni access OCW materials to pursue lifelong learning.

MIT has also benefited from the attention it has received. A large number of media outlets from around the world have featured OCW. For example, Wired (Diamond, 2003) reported that, before OCW,

no institution of higher learning had ever proposed anything as revolutionary, or as daunting . . . . MIT earned the distinction as the only university forward-thinking enough to open-source itself.

Global Impacts

For users in developing regions of the world such as sub-Saharan Africa where Internet access is cost-prohibitive, unreliable, or nonexistent, OCW helps to bridge the “digital divide” through its mirror site program on external drives, and there are more than 430 of these sites.

Through the regular OCW site, YouTube, and these mirror sites, over 200 million people have accessed the content more than 500 million times. Many (50 percent) are students at other institutions, both college and pre-college, and others are “self-learners” looking to enrich their professional and personal lives (45 percent). As an example of self-learners, Jean-Ronel Noel and Alex Georges from Haiti wanted to develop solar panels for their country but needed guidance in electrical engineering. They found it through OCW. Noel told the OCW staff,

I was able to use OCW to learn the principles of integrated circuits. It was much better than any other information I found on the Internet.

Their company, Enersa, has made solar-powered LED lighting available in almost 60 Haitian towns and remote villages (d’Oliveira et al., 2010).

While teachers currently account for five percent of those who access OCW, their use has a multiplier effect when used with their students. Educators have described a variety of ways in which they incorporate OCW material into their classes. For example, Triatno Yudo Harjoko, head of the Architecture Department at the University of Indonesia, said that to redesign the curriculum he and his colleagues turned to MIT OCW as an immense comparative database (d’Oliveira et al. 2010):

We try to understand how the courses are formulated and what the expected outcomes are. This gives us an important perspective on the learning process.

Concluding Remarks

OCW was transformed from an informed leap of faith to a functional enterprise that serves learners all over the world and returns benefits to MIT. It is a “bold creation” (Bowen, foreword to Walsh, 2011) that changed the equation for e-learning from the obsession with commercialism of the dot-com era to a demonstration of the enormous value in freely sharing knowledge produced by an academic institution. The one million people who access OCW every month illustrate the demand for high-quality teaching materials among students, self-learners, and educators. As we live through the pandemic, resources such as OCW have become even more valuable, leading to a 60 percent increase in website visits from all over the world during the peak quarantine period of April-May 2020.

OCW moves into its next 20 years with a renewed commitment to share the MIT curriculum with vibrancy and currency as it evolves, highlighting materials on big themes like the future of computing, sustainability, and social justice. A new platform currently in development will better support learners on mobile devices and those with sporadic Internet access, substantially enhance the search tools millions of learners use to find learning opportunities, and foster greater adoption and adaptation of OCW materials by educators in their teaching. And, OCW looks forward to prioritizing collaborations with others in the broad OER ecosystem (that OCW itself played a role in seeding) to build greater educational equity, through adapting and customizing content to meet the needs of specific learning communities. In all these ways and more, MIT is building upon OCW’s 20-year foundation of unlocking access to knowledge.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Curt Newton, Krishna Rajagopal, and Sanjay Sarma for valuable comments. Portions of this text were originally published in an article by Shigeru Miyagawa in The Bridge 46(3):5-11. © National Academy of Engineering.

References

Abelson H. 2008. “The creation of OpenCourseWare at MIT.” Journal of Science Education and Technology 17(2):164–174.

Abelson H., Miyagawa S., Yue D. 2012. “MIT’s ongoing commitment to OpenCourseWare.” MIT Faculty Newsletter, Vol. XXIV No. 4, March/April. Available at http://web.mit.edu/fnl/volume/244/fnl244.pdf.

Diamond D. 2003. “MIT everywhere.” Wired, September 1. Online at www.wired.com/2003/09/mit-2/.

d’Oliveira C., Carson S., James K., Lazarus J. 2010. “MIT OpenCourseWare: Unlocking knowledge, empowering minds.” Science 329 (5991):525–526. Available at http://science.sciencemag.org/content/329/5991/525.full.

Goldberg C. 2001. “Auditing classes at MIT, on the web and free.” New York Times, April 4.

Klopfer E., Miller H., Willcox K. 2014. “OCW educator: Sharing the how as well as the what of MIT education.” MIT Faculty Newsletter, Vol. XXVI No. 5, May/June. Available at http://web.mit.edu/fnl/volume/265/fnl265.pdf.

Lerman S. 2004. “OpenCourseWare update: Beyond the anecdotes.” MIT Faculty Newsletter, Vol. XVI No. 5, April/May. Available at http://web.mit.edu/fnl/vol/165/lerman.htm.

Lerman S., Miyagawa S. 2002. “Open course ware: A case study in institutional decision making.” Academe Online88(5), Sept.-Oct.

MIT News Office, “Provost announces formation of council on educational technology.” September 29, 1999.

MIT Task Force on Student Life and Learning. 1998. http://web.mit.edu/committees/sll/

Vest C. M. 2004. “Why MIT decided to give away all its course materials via the Internet.” Chronicle of Higher Education, online edition, January 30. Available at http://web.mit.edu/ocwcom/MITOCW/Media/Chronicle_013004_MITOCW.pdf.

Walsh T. 2011. Unlocking the Gates: How and Why Leading Universities Are Opening Up Access to Their Courses (see chapter “Free and Comprehensive: MIT OpenCourseWare”). Princeton University Press. Available at www.sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/UNLOCKING_the_GATES_text-only.pdf.

- Available at http://web.mit.edu/facts/mission.html. [↩]