Non-Native English-Speaking Graduate Students Still Face Significant Disadvantages

Eric GrunwaldAlmost half of MIT graduate students arrive from outside the United States and immediately enter a communication-intensive culture here in which they must understand lectures, read voluminous amounts of material, speak (and comprehend) in class and lab meetings, write papers and lab reports, and begin applying for internships and jobs. They then move toward writing proposals, a thesis, and journal articles and presenting at conferences and being teaching assistants, among other tasks. And although in many ways and from many places, students arrive with higher skills in English today than previously, many students – even those who have graduated from English-instruction undergraduate institutions – still have significant gaps in their linguistic skills and cultural knowledge about communication that impact their ability to participate fully and succeed at MIT and beyond.

This situation is reflected not only in the results of the annual English Evaluation Test (EET) – established in 1983 at the behest of faculty – but also in the results of the 2023 MIT Graduate Communication Survey as well as a recent meta-study (Amano, et. al. 2023) showing that non-native English speakers (NNESs) still face significant disadvantages in conducting and communicating their research compared to their native-English-speaking counterparts (NESs).

As director of MIT’s English Language Studies (ELS) group, I write to alert you to this ongoing need, and in the hopes of opening a broader dialogue on the subject. For now, though, I urge faculty and the administration to work to:

- Help NNES students understand the importance to their success at MIT and beyond of improving their communication skills in English,

- Help NNES students understand what is really involved – time, engagement, feedback, and practice/revision – in achieving that improvement, and

- Try to make it easier and more desirable for students to do that by affording them time and space to take the ELS classes recommended to them on the basis of the English Evaluation Test.

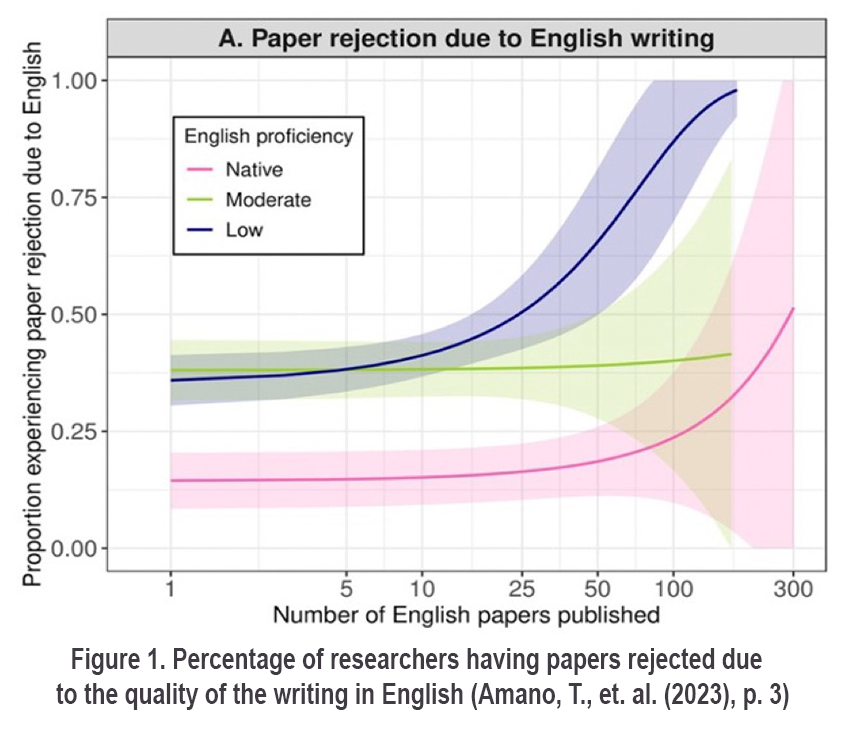

In a paper published last year, Amano, et. al. found that it takes early-career NNESs almost 50% longer than native English speakers (NESs) to read a journal paper and 50% longer to write one as well. Given the number of papers that students must read, that first discrepancy cumulatively represents enormous amounts of extra time and effort. And while MIT students are not immediately writing papers for publication, the finding suggests the greater difficulty in writing for NNESs generally. And these discrepancies stretch beyond the reading and writing processes to affect students’ wallets as well as others’ time: NNESs, Amano found, generally ask others to edit their work more often as a favor and also pay professionals more often to edit – not a negligible expense. Worse is that NNES researchers face rejection of submitted papers for the quality of the writing in English three times as often as do native speakers (Figure 1).

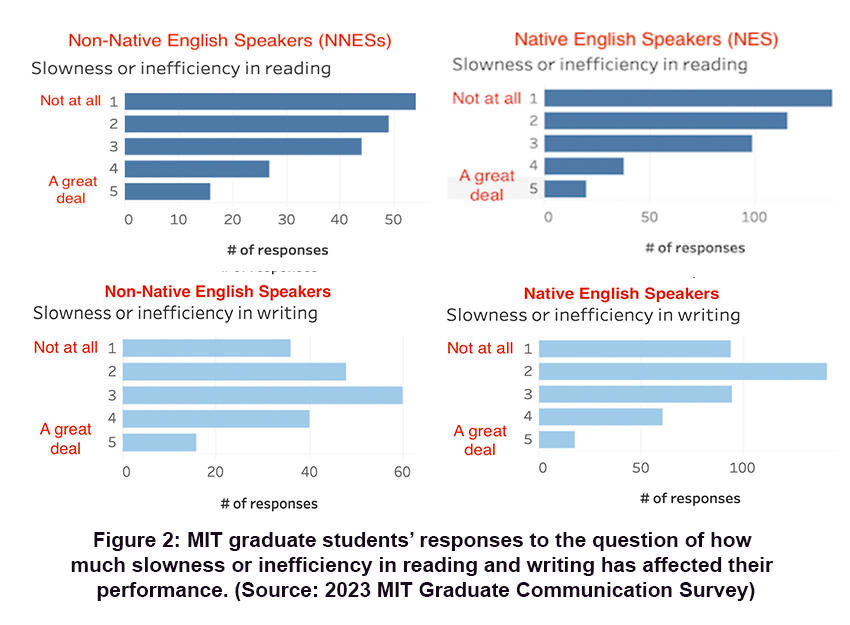

Students’ responses to the 2023 MIT Graduate Communication Survey – which I conducted last year with Dr. Elena Kallestinova, director of MIT’s Writing and Communication Center – echo these discrepancies. Of the over 7,200 graduate students sent the survey, almost 14% (996) responded, and NNESs reporting much greater difficulty in, first of all, reading and writing than their NES counterparts (Figure 2). For example, almost a quarter (23%) report a significant impact of slowness or inefficiency in reading (a rating of 4 or 5), compared to only 14% of native speakers. Adding in responses of tangible impact (a rating of 3), almost half (46%) of NNESs report their performance being affected, compared to only 38% of NESs.

With writing, almost 30% of NNESs report a significant impact of slowness or inefficiency in writing on their overall performance, whereas 20% of NESs report this. Again adding in ratings of 3, almost 60% of NNESs report a tangible impact, compared to 46% for NESs.

Students’ assessments of their own skills help explain these results. Three times as many NNESs (13%) rate their academic writing skills as “weak” or “very weak” as do native speakers (4.5%), while at the other end of the scale, less than half of NNESs (49%) rate their writing skills as “strong” or “very strong,” compared to three-fourths of native speakers (75%).

And while students’ perceptions of their own skill levels can either be too low or too high, these perceptions have their own significant impacts. When students were asked how much anxiety about their communication skills impacted their performance at MIT, similar gaps arise. In academic writing, one-fifth of non-native English speakers say that anxiety about their skills has significantly impacted their performance, and adding in tangible impact (a rating of 3 out of 5), the number rises to almost half (46%). Compare those numbers to 12% and 36%, respectively, for native speakers.

The discrepancies for oral communication are even starker. Almost a third (31%) of NNESs say that anxiety about their oral academic skills has significantly impacted their performance, and including tangible impact (3 out of 5), that percentage reaches 55%. The analogous figures for native speakers are 19.5% and 44%, respectively. Similarly, a full one-fifth of NNESs rate their oral academic communication skills as “weak” or “very weak,” compared to only 6% for NESs.

While we did not ask as much about what those impacts were, Amano, et. al.’s findings suggest some possible answers. They found that almost one-third of early-career NNESs always or often declined to attend conferences due to language barriers (pp. 6-7), and almost half always or often choose not to give oral presentations due to such barriers. And when they do present, it takes them almost twice as long (93% more time) to prepare as it does their NES colleagues.

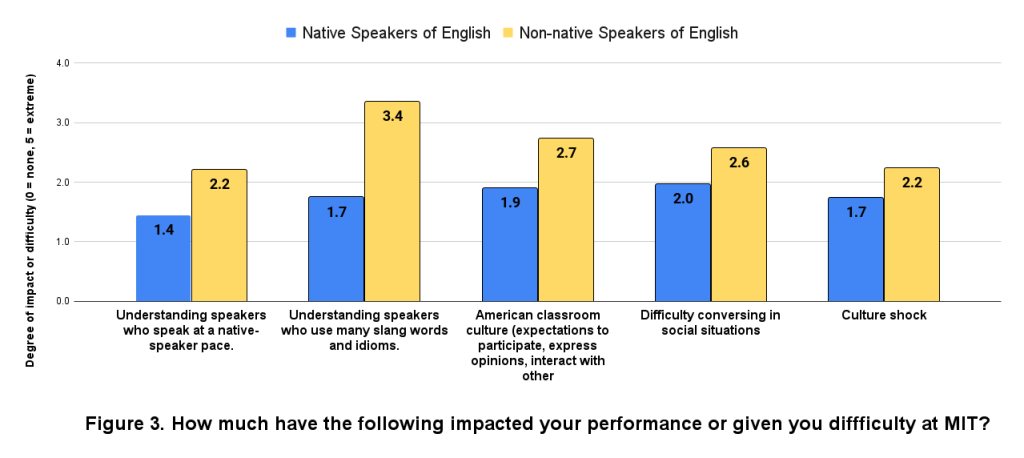

Comprehending spoken English at MIT is also as great a problem for many NNES students as is speaking. As can be seen in Figure 3, NNESs (yellow) face much greater difficulty than NES students in understanding native speakers speaking at a normal pace and using idiomatic language (which most of us do much more than we might realize). Indeed, these results echo comments by several first-year students in ELS’s intermediate listening, speaking, and pronunciation course that they understand perhaps 60% of their lectures their first year.

Finally, cultural issues pose great, unique challenges to NNESs. As Figure 3 also shows, understanding and adapting to American classroom culture, in which much more interaction and engagement is expected than in many other cultures, is also a challenge. Moreover, significant differences exist in the norms and expectations in communication such as the structure of documents and talks (e.g., placement of key messages), lexical register (properly formal or informal vocabulary), and even how to engage in small talk at conferences, which serves important professional and social purposes.

What Can Be Done at MIT?

The English Evaluation Test (EET) was created to address such issues at the behest of faculty who were frustrated that many NNESs students could not write sufficiently clear theses (which advisors then often had to – and still often have to – edit significantly) or could not participate sufficiently well in lab meetings. Although NNES students take a standardized test such as the TOEFL or IELTS for admission to MIT, such tests have been shown not to be reliable indicators of academic readiness. Moreover, since those test scores are composites of separate scores for the four “core” skills, students may arrive with adequate skills in some areas but not in others. My colleagues in English Language Studies and I thus administer the EET, a four-part instrument tailored for MIT students, in August and again (on a much smaller scale) in January and provide not only scores on various skills but corresponding recommendations for ELS credit-bearing subjects that address these skill gaps.

Only a small percentage of students end up taking those classes, however. For example, this academic year, 298 students took the EET, and about 25% of those, or 72 students were recommended for a high-intermediate class, which is designed to be taken during students’ first year. Such a recommendation comes out of scores in the “Limited” range, meaning that the student will face significant difficulties completing regular academic communicative tasks that year. Seventeen students, or less than a quarter of those recommended, took those classes this year.

Recommendations for our advanced classes numbered even more (~120) – classes that focus on writing or speaking in particular contexts such as a thesis or conference presentation and that are thus designed for students’ second year or beyond, when they can use their research work for the assignments in our classes – but are fulfilled at an even lower rate.

Of course, while the Institute mandates the test for international students, it leaves the decisions – in the spirit of decentralization and departmental agency – of what to do with those recommendations to departments, advisors, and students. Some departments require students to fulfill those requirements, but most do not. So why do students not take the classes that the Institute tells them are necessary for them to be able to succeed fully here? While I am still coming to understand the many forces and factors at work here, I have come in my twelve years at MIT to believe that most students do not understand how important communication skills are going to be to them even in a STEM subject, or if they do, they feel too much pressure to focus on their disciplinary classes and their research. In short, without departmental and faculty encouragement or requirement, many will not find the time or impetus to take these subjects.

Moreover, while undergraduate enrollments in ELS classes have rebounded to pre-Pandemic levels, graduate enrollments for some reason have not. Many students do want to take these classes, however, and in the MIT Graduate Student Survey, 93 NNESs out of 225 said a class had been recommended for them. Just under a quarter had taken those classes, and another 15% said they planned to take one. Of those who had not taken a class, several said that improving those skills was not as important to them as their other academic priorities, while others said that the classes conflicted with their other academic or research work.

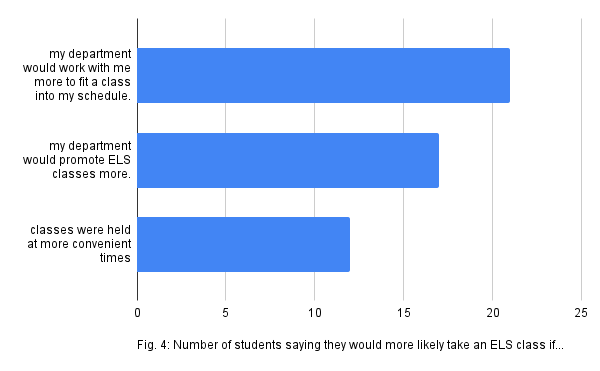

However, as Figure 4 shows, many are interested and say they would be more likely to take an ELS class if their departments and faculty helped them fit the courses into their schedules or if their departments promoted the classes more to them

Departmental and faculty encouragement is also necessary because, due to cultural factors, the very people who need such support are the very ones who are less likely to do so. In our survey, 45% of NNESs said that “feeling shy about seeking out communication support” has tangibly affected their performance at MIT, compared to less than 30% for native speakers.

I do not pretend to understand all the factors that go into determining students’ curricula, and of course students need to be in the lab to do research. One idea might be to allow ELS classes to count as elective credits toward graduation, which apparently not all departments do. Another would be to encourage students to use their elective credits to take an ELS class rather than, say, an “extra” math class that may not be crucial for that student’s work.

It can be easy to underestimate how much a second-language student has to adjust on a daily basis to communicate clearly. And tangible improvement in language and communication skills requires dedicated attention (i.e., over the course of a semester), practice, detailed feedback, and revision. One cannot “phone it in,” absorb skills by sitting in occasionally, or improve skills tangibly with self-study (which inevitably falls by the wayside). Ultimately, though, it seems to me that granting a student admission implies to them that either they are already equipped to do all the work asked of them or else will be given the tools to do so once they get there. If once they are here, though, we tell students that they are not quite prepared but then do not afford them the time and space to utilize the resources available to them to become so, then we are, if not setting them up for failure or at least significant difficulty, depriving them of the chance to compete on a fair playing field. We are also ultimately depriving the rest of the Institute of the full range of the intelligence and creativity that these students have to offer.

I had the chance in October to ask President Kornbluth how important she thought linguistic and communication skills are for students, and she said: “When you’re competing in the job market as an MIT student or new graduate, potential employers will almost take for granted your technical and scientific qualifications. But they’re also looking for people who can express complex ideas in compelling ways and work effectively with everyone from co-workers to investors. In other words, to develop your own potential, learning to write and speak clearly and professionally is just as important as any technical skill.” I thus invite the Institute and faculty to explore ways to afford non-native-English-speaking graduate students the time and space to equip themselves communicatively and linguistically to tackle all the challenges and opportunities that MIT lays before them.

I also invite you to explore the full results of the Survey at https://cmsw.mit.edu/communication-survey-2023/. And I invite anyone and everyone to reach out to me to discuss further how we in ELS can aid in these endeavors.

References

Amano, Tatsuya, et. al., The manifold costs of being a non-native English speaker in science PLOS Biology, July 2023, pp. 1-27.

The 2023 MIT Graduate Communication Survey. MIT’s English Language Studies Group and the Writing and Communication Center. https://cmsw.mit.edu/communication-survey-2023/