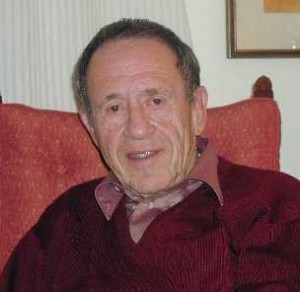

Leo Marx died a few weeks ago at the advanced age of 102. He was one of the leading scholars of his generation in America, a classic humanist, using the literature of great minds and the contingencies of history to think through current problems about the effects of technology on society.

With the exception of Noam Chomsky, Leo was probably the most significant thinker to grace the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences in the last 50 years. But rather than detail his books and articles, ably done elsewhere, I want to write about him as a colleague, for there, too, he exemplified the best of our profession. To begin with, he was a brilliant teacher; his remarks in the classroom illuminated the words of many an American author for generations of students. Moreover, he was always willing to share his love of writers like Emerson and Thoreau and to visit one’s class as a guest lecturer. Those occasions transformed the quotidian into celebrations, full of light and pleasure for everyone, as he communicated his joy in the work and his delight in enthralling the rest of us.

Not that we agreed about everything. Although he had been radical in his school days, an admiring student of F. O. Matthiesson at Harvard, for a long time he had no women writers on his syllabi in American literature. He staunchly supported women in the workplace, but declined to include them on his reading lists. I argued the case for Sarah Orne Jewett’s New England classic Country of the Pointed Firs at the very least, and urged other women writers of the nineteenth century on him. Eventually, under pressure from students as well, he yielded the point; but he asked me to guest lecture on Jewett at first and it took a while for him to thoroughly appreciate this part of the intellectual world. But he did change his mind and his personal literary canon expanded as he grew older.

Leo was exceptionally kind to younger scholars and shared his influence wherever he could, with a letter or a recommendation or a contact where it would do the most good.

He would read the jejune works of those who came to admire him even when he had no institutional responsibility to do so – and then took the time to give good practical succinct advice. Open to most everyone who called, he gave his time and attention to hundreds of would-be scholars, teachers, and students over the years. He did not protect himself from visitors the way most busy and influential scholars do but was courteous to the young and unknown, the awkward and shy, the fearful and bold alike.

Leo was also a loving and thoughtful friend. I still cherish the MIT sweatpants that he and Jane (his incisive partner of 62 years) brought me in the hospital after a hip replacement. He gave me essential advice on the first chapter of my last book. I daresay there are hundreds of people today who could tell such tales of his generosity. Besides being a mensch, he wrote deeply meaningful essays and books about things that matter, and his inspired writings will live on long after these stories of his kindnesses have faded with the tellers.